Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) Biology

General Biology:

The Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) is a large and brightly colored butterfly with black-veined, orange-paneled wings. It’s a very commonly seen across the United States, southern Canada and Mexico. This relatively large butterfly is among the most easily recognizable butterfly species in North America. They have two sets of wings and a wingspan of three to four inches. The underside of the wings is pale orange. Male monarchs have two blackspots in the center of their hind wings, which females lack. These spots are scent glands that help males attract female mates. Females have thicker wing veins than males. The butterfly’s body is black with white markings.

The Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) is a large and brightly colored butterfly with black-veined, orange-paneled wings. It’s a very commonly seen across the United States, southern Canada and Mexico. This relatively large butterfly is among the most easily recognizable butterfly species in North America. They have two sets of wings and a wingspan of three to four inches. The underside of the wings is pale orange. Male monarchs have two blackspots in the center of their hind wings, which females lack. These spots are scent glands that help males attract female mates. Females have thicker wing veins than males. The butterfly’s body is black with white markings.

Monarch caterpillars are striking as well and striped with yellow, black, and white bands, and reach lengths of two inches (five centimeters) before metamorphosis. They have a set of antennae-like tentacles at each end of their body. The monarch chrysalis, where the caterpillar undergoes metamorphosis into the winged adult butterfly, is a beautiful seafoam green with tiny yellow spots along its edge.

What makes the monarch butterfly particularly interesting is that it combines the usual four-stage butterfly life cycle with one of the longest migrations of the insect world. Individual monarch butterflies are known to travel thousands of miles in their fall migration.

Range:

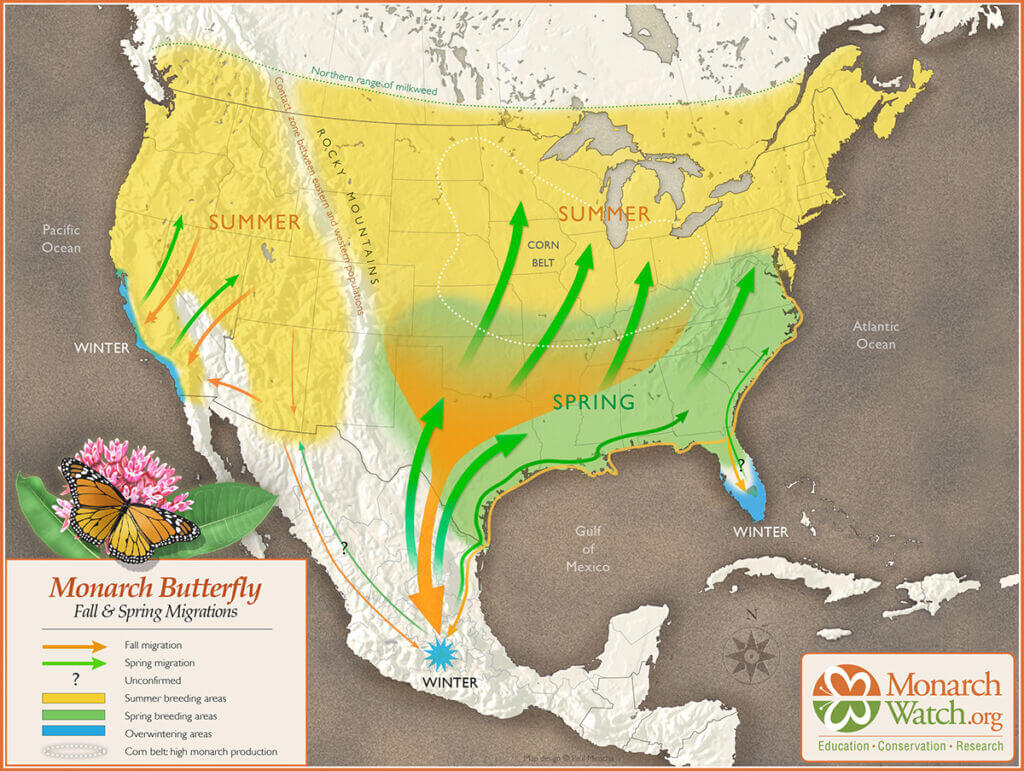

Monarch butterflies are found across North America wherever suitable feeding, breeding, and overwintering habitat exists. They are divided into two populations separated by the Rocky Mountains, called the eastern and the western populations.

Whether monarchs are present in a given area within their range depends on the time of year and available habitat. In the summer they range as far north as southern Canada. In the fall eastern populations migrates to the cool, high mountains of central Mexico and the western population migrates to coastal California, where they spend the entire winter.

The population east of the Rocky Mountains contains most of the North American monarch population, which completes its northward migration through successive generations. They are most abundant through the central United States along this migratory corridor. In spring the monarchs leave their overwintering grounds in Mexico and migrate north into Texas and the Southern Plains, then up through the Northern Plains and the Midwest, and finally up into the Great Lakes region. By late summer, eastern monarchs have spread north into Canada and eastward from the central migratory corridor throughout the Northeast and Southeast states.

From September into early October, southern migration to Mexico begins, with the majority of monarchs following the reverse path south along the central migratory corridor. Monarchs from the Northeast head south along the Atlantic coast, concentrating in the states that make up the Delmarva Peninsula between the Atlantic Ocean and the Chesapeake Bay on the journey. Florida is a stop for many monarchs before they fly over the Gulf Coast to Mexico. A much smaller population of monarch butterflies lives west of the Rocky Mountains. During summer, western monarchs live in canyons or riparian areas of the West, Southwest, inland California, and the inland Northwest states as far north as British Columbia. A small number of monarchs can be found in the coastal Pacific Northwest during summer months. Instead of making the long journey to Mexico, western monarchs typically migrate as far south as coastal areas of central and southern California.

There are populations of monarchs in Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and some islands of the Caribbean, as well as in New Zealand. Monarchs may have been blown to these places in storms or naturally dispersed there by island-hopping, or they may have been introduced by humans. These populations are not part of the annual migrations on the North American mainland.

Diet:

Monarchs, like all butterflies, have a different diet during their larval caterpillar phase than they do as winged adults. As caterpillars, monarchs feed exclusively on the leaves of milkweed, wildflowers in the genus Asclepias. North America has several dozen native milkweed species with which monarchs coevolved and upon which they rely to complete their life cycle.

Milkweed produces glycoside toxins to deter animals from eating them, but monarchs have evolved immunity to these toxins. As they feed, monarch caterpillars store up the toxins in their body, making them taste bad, which in turn deters their predators. The toxins remain in their system even after metamorphosis, protecting them as adult butterflies as well. As adults, monarchs feed on nectar from a wide range of blooming native plants, including milkweed.

Life History:

Monarchs lay their eggs exclusively on milkweed plants. It takes three to five days for the eggs to hatch. After hatching and consuming their empty egg case, the caterpillars feed on the milkweed. The caterpillars grow and molt several times over roughly a two-week period and then form a chrysalis to undergo metamorphosis. After approximately another two weeks within the chrysalis, they emerge as adult butterflies.

Most adult monarchs only live for a 2 to 5 weeks. As adults they search for food in the form of flower nectar, search for mates, and require additional milkweed to lay their eggs on. The last generation that hatches in late summer delays sexual maturity and undertakes the fall migration. This migratory generation can live upward of 8 to 9 months.

The annual monarch life cycle and migration begins at the monarchs’ overwintering grounds in Mexico (for the eastern population) and the central to southern California coastal region (for the western population). Around March, the overwintering monarchs begin their journey north. Once migration begins, monarchs become sexually mature and mate. The females begin their search for milkweed plants on which to lay eggs. After mating and egg-laying, the adult butterflies die and the northward migration is continued by their offspring. It takes three to five generations to repopulate the rest of the United States and southern Canada during the summer months, until the final generation of the year hatches in the fall and begins the return journey to the overwintering grounds.

The monarch migration is one of the greatest phenomena in the natural world. Monarchs know the correct direction to migrate even though the individuals that migrate have never made the journey before. They follow an internal “compass" that points them in the right direction each spring and fall. A single monarch can travel hundreds or even thousands of miles.

Conservation:

It is estimated that the monarch population has declined by approximately 90 percent since the 1990s. Monarchs face habitat loss and fragmentation in the United States and Mexico. More than 90 percent of the grassland ecosystems along the eastern monarch’s central migratory flyway corridor have been lost, converted to intensive agriculture or urban development. Pesticides are also a danger. Herbicides kill both native nectar plants where adult monarchs feed, as well as the milkweed used by caterpillars. Insecticides can kill the immature and adult monarchs themselves. Changing weather patterns have altered the timing of migration as well, posing a risk to monarchs during migration and while overwintering.

One easy way to help monarchs is to plant a pesticide-free monarch habitat garden filled with native milkweed and nectar plants. North America has several dozen native milkweed species, with at least one naturally found in any given area. Use these regional guides to the best native nectar plants and milkweed for monarchs in your area. Listed plants are based on documented monarch visitation, and bloom during the times of year when monarchs are present, are commercially available, and are hardy in natural growing conditions for each region. You can get information about additional butterfly and moth host plant species native to your zip code using the Native Plant Finder.

Planting locally native species is the best option for helping monarchs because monarchs coevolved with native plants and their life cycles are in sync with each other. In the last decade tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica), a plant not native to the United States, has become an increasingly popular way to attract monarchs in garden settings. Tropical milkweed is ornamental and easy to grow and has become one of the most available milkweed species in nursery trade. Monarchs happily lay eggs on it. Despite these qualities, when planted in southern states and California, tropical milkweed can encourage monarchs to skip their migration and continue to breed through the winter, potentially putting them at risk for disease and other complications that they would have been avoided by migrating. Most monarch conservation groups encourage planting native milkweed and cutting back tropical milkweed in the fall to encourage monarch migration.

Above information is adapted from the National Wildlife Federation. Visit their site for more conservation information.